FEMININITY in the Public Sculpture - GDR cultural policy and femininity in public

Berlin has a long tradition of artistic engage- HIGHLIGHTS ALONG THE ROUTE ment with public spaces, buildings, and civil engineering works. As a result, a plethora of sculptures, murals, statues can be found throughout the city. Some objects are hidden; others are placed prominently on walls, in parks, or on streets. Public artworks allow people to encounter art outside museums and function as open invitations to explore their meaning and revel in their wonders. Pankow and Lichtenberg o er public

art tours by foot or bike. Participants learn about the creation of the works and their materials along with the social background, life, and output of the artists themselves.

This tour takes you through the districts of Niederschönhausen, Pankow, Prenzlauer Berg, Lichtenberg and Friedrichsfelde to see representations of femininity in the public sculpture of the GDR era. In East Germany, equal rights for women were enshrined in law and propagated everywhere – including the fi ne arts. Starting in the late 1940s and continuing throughout the 1950s, symbolically charged images of mothers and women workers were cast in bronze or carved in stone and put on display in cities. Over the decades that followed, East German streets, squares, and parks became filled with less severe and more everyday scenes: female nudes, athletes, and mothers with children. The tour will explore the di erent styles of the artists who sculpted images of women in the GDR.

Station 1: Mother Homeland (Mutter Heimat), Artist: Iwan Gawrilowitsch Perschudtschew (1915–1987)

Location: Soviet Memorial, Schönholzer Heide, Artist: Iwan Gawrilowitsch Perschudtschew (1915–1987), Date: 1947–1949 Material: bronze

At the end the Second World War, the Soviet military administration erected a memorial to Soviet soldiers who died in the Battle of Berlin. The motifs in Mother Homeland are typical of the Soviet Union’s monument culture. The mother gure symbolizes love for her homeland and represents all mothers mourning sons who died in the war. She stands behind a dead soldier laid out in front of her on a massive base. She wears a traditionally cut pleated dress, with a patterned cloth draped over her shoulders and arms. Her right hand touches a large laurel wreath, while her left hand holds the Soviet flag, which serves as a shroud covering her son’s corpse. The mother’s face is tired but composed. The realistic representation and the hyperbolic symbolism, along with the focus on “home”, are common stylistic devices of socialist realism, which shaped the art of many Eastern European countries. The depiction of Mother Homeland and the virtues of strength and love ascribed to her recall a central motif of Christian iconography: the Pietà.

In this regard, the mother gure represents traditional Christian values. Her demure femininity, hidden behind her dress, stands in the tradition of antique depictions of ancient goddesses. Perschudschew’s work presents the heroic image of a woman who suffers from the death of her son while radiating composure and strength.

Station 2: Kauernde (Crouching Woman), Artist: Rolf Winkler (1930–2001)

Location: Hermann-Hesse-Straße 18/Güllweg, green area, Kauernde (Crouching Woman), Artist: Rolf Winkler (1930–2001), Date: 1983, Installation: 1985, Material: concrete

Rolf Winkler’s Crouching Woman is located on a meadow north of Niederschönhausen Palace Park. The gure is perched on a block of stone, her upper body leaning forward, her arms and legs bent and drawn close to her sides. Her head is turned, with the right half of her face resting on her knees. At first glance, it seems as if the woman might be writhing in pain. But her face is relaxed, and her eyes and mouth are closed. Her shoulder-length hair falls to the side, revealing a long neck. It is interesting to contemplate the sculpture’s play of forms. The closed, self-contained form of the body resembles an oval. The great convex arch of her back stands in contrast to her bent arms and legs.

Winkler’s ability to balance calm and tension, the concave and the convex, triangle and oval, is on full display here. The work’s egg-like form symbolizes the origin not only of sculptural art but of life itself. In this way, Winkler suggests that the life that dwells within the woman is archetypical.

Winkler belongs to the second generation of sculptors in the GDR, who followed the example of their teachers and remained committed to realistic sculpture. After an apprenticeship as a stone sculptor in Dresden, Winkler studied at the Berlin-Weißensee Academy of Art with Heinrich Drake, an important advocate of realistic sculpture in the GDR. But Winkler’s artistic language departs somewhat from the example set by Drake. Crouching Woman is not a typical female nude – idealized and benevolent. Rather, the sculpture’s gure is reserved, with plays of opposing forms.

Station 3: Drei Frauen (Three Women), Artist: Carin Kreuzberg (*1935)

Location: Green area along Elisabethweg/Ossietzkystraße, Drei Frauen (Three Women), Artist: Carin Kreuzberg (*1935), Date: 1979, Installation: 1993, Material: Bronze

Three Women face each other in silent dialogue. Inner peace and spirituality emanate from their tall, graceful gures. Their owing contours and smoothed surfaces buttress the uniform gliding movements of their vertical forms. A closer look reveals subtle differences between the gures. One woman’s smile is restrained. Standing with both feet rmly on the ground, she spreads her arms and turns her palms outward. The gazes of the other women are lowered slightly, and they stand in slight contrapposto as they shi their weight from leg to leg. The gures’ arms alternate, suggesting movement and liveliness. One woman’s arms are behind her back; the other’s rest on the front of her thighs. The sensitive interplay of gestures creates a subtle dynamic between the three women.

Carin Kreuzberg studied sculpture with Walter Arnold and Heinrich Drake – advocates of expressive sculpture and important representatives of realism in the fine arts. Like her teachers, she reduces her expressive form to a laconic formal language. The postures of the gures and the positions of the legs and feet recall female representations in Egyptian art. The muted facial expressions and gestures, the powerful simplicity, and the unity of composition are features of Greek sculpture from ancient and early classical periods. Moreover, the sculpture alludes to the Three Graces, well-known gures in Greek and Roman mythology and a common subject in painting and sculpture. But Kreuzberg’s sculpture shows a different understanding of public femininity: her women are at peace, spiritually grounded, and yet full of life.

Station 4: Mutter mit Kind (Mother with Child), Artist: unknown

Location: Leonhard-Frank-Straße, Bürgerpark Pankow, Mutter mit Kind (Mother with Child), Artist: unknown, Date: 1984, Material: sandstone

The gures of Mother with Child recline on the grass of the Bürgerpark in Pankow. The pose belongs to a well-established tradition in sculpture. For centuries artists have used it to study human physiognomy and explore the ways in which their subjects connect with the earth. Here, however, the focus is primarily on the intimate relationship between a mother and her daughter. The mother’s head is angled towards the child – perhaps they are talking or enjoying a moment of silence together. The mother’s forearms rest on the ground, while her legs support the child. If you look at the sculpture long enough, the mother seems to be rocking the child back and forth. The composition of their heads, the juxtaposition of their bodies and their eye contact hold tension in the space between them, even as the sculpture emanates calm and gravitas. The blockiness of the sculpture, the roughly worked limbs, and the coarse, porous surface betray its sandstone origins.

Mother with Child was created at a time when East German artists had more freedom than they did during the era of mandatory socialist realism in the 1950s and 60s. The mother-child motif was common in the sculpture of the GDR and frequently used for parks, green areas, and pedestrian zones. It is the visual expression of the dominant parenting model in the GDR, in which mothers were the primary caregivers for children and families.

Pankow’s Bürgerpark has been a popular destination since its founding, in 1907. The sculptures and statues located within it provide a representative collection of the sculptural art of the GDR and the post-reunication period.

Station 5: Berliner Mädchen (Berlin Girl), Artist: Gerhard Rommel (1934–2014)

Location: Heinz-Knobloch-Platz, green area, Berliner Mädchen (Berlin Girl), Artist: Gerhard Rommel (1934–2014), Date: 1961, Installation: 1962, Material: Bbronze

The best word to describe the gure in Gerhard Rommel’s Berlin Girl is Göre, or brat: cheeky, self-condent, standing with both feet rmly on the ground, she gazes deantly into the distance. To aid her vision, the girl raises her head slightly and puts her hand on her forehead. Her hair is tied into two bushy pigtails and her snub nose underscores her girlish character. She casually puts her right hand in her pant pocket. Her bold and self-possessed demeanor is also reected in her clothes: a thin shirt and tight trousers cover her slender youthful body. The slightly arched back and rounded outstretched belly apostrophize her bearing. Maybe she is looking for her date in the park. Anyone who crosses her path is bound to get a mouthful.

The bronze sculpture was erected in 1962 on a square renamed in 2005 aer the writer Heinz Knobloch, who died two years earlier. The sculpture’s realism shows the inuence of Fritz Cremer and Heinrich Drake, important representatives of the realist school with whom Rommel trained in the 1950s and 60s. The sculpture’s femininity is self-assured, sassy, charming and literally forward-looking. Though the everyday motif that Rommel created was typical for the squares and pedestrian zones of its time, his handling of the subject is evidence of East Germany’s relative openness when it came to depictions of women in public space.

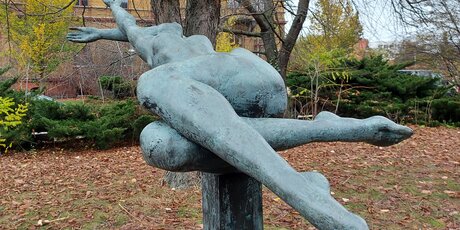

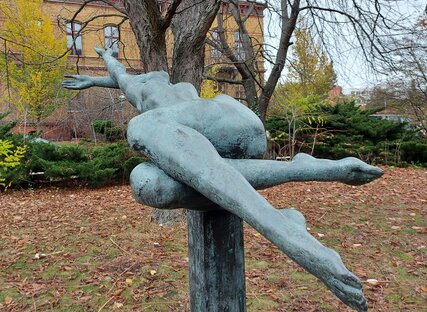

Station 6: Große Badende (Large Bathing Woman), Artist: Wieland Förster (*1930)

Location: Fröbelstraße 17/Diesterwegstraße, next to house no. 2, Große Badende (Large Bathing Woman), Artist: Wieland Förster (*1930), Date: 1971–1973, Material: bronze

The figure in Large Bathing Woman does not assume any of the positions that are typical in sculpture – sitting, standing, reclining. On the contrary, the figure is positioned at a diagonal in space and seems to remain somewhere between swimming and oating. When walking around the sculpture, one notices the dynamic force of her arms and legs. Partly angled, partly stretched, they advance and create powerful lines and geometric shapes. The waist, turned 90 degrees to the side, indicates a twisting movement. The expansive pelvis acts as a hinge, giving the impression of a body whose upper and lower halves are rotating in opposite directions. By contrast, her face appears relaxed: her head is slightly bent back, and her eyes and mouth are closed.

The figure in Large Bathing Woman seems to be enjoying the moment in the water. The lush shapes in the pelvis and chest area are pleasing to the eye. Her swelling and ebbing forms reveals an energetic rhythm reecting both her inner vitality and the movements of the water. Förster’s modeling merges the gure with its environment, an approach to sculpture he developed in the 1970s and applied many times since.

The naturalism of the design betrays the inuence of Walter Arnold and Fritz Cremer, with whom Förster studied in the 1950s and 1960s. But Förster also went beyond their realism to something more dynamic and expressive, a figure representing his own ideal of feminine vigor and beauty. Though public nude sculptures were commonplace in the GDR, some East Germans criticised Large Bathing Woman for its blatant eroticism.

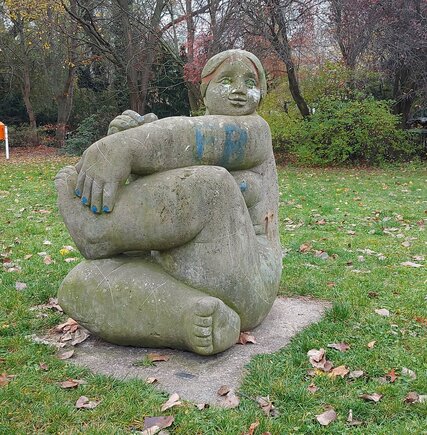

Station 7: Felicia, Artist: József Seregi (*1939)

Location: Northern end of Anton Saefkow Park, Villa am Fennpfuhl (registry office), Felicia, Artist: József Seregi (*1939), Date: 1987, Installation: 1988, Material: Reinhardtsdorf sandstone

The name Felicia is Latin for “the lucky one”, and the gure in this sculpture looks the part. Sitting comfortably on the ground, her face is friendly and her full mouth displays a welcoming smile. Curved lines in the sandstone mimic the texture of hair tied into a braid. The bent arms and legs form a fascinating contrast to the rounded arch of the back. In keeping with its times, Felicia’s forms are freer than was common in the early years of the GDR. Its true-to-life naturalness and curvaceousness eschews the idealizing tendencies of sculpture since antiquity. The gure’s body, though formed from a cube, displays an artless joie de vivre that is perfectly in tune with its surroundings. The sculpture was created for the 2nd International Berlin Sculptor Symposium, which was held in 1987 in Schlosspark Berlin-Buch under the motto “Poetry of the Big City”.

Station 8: Große Liegende (Large Reclining Woman), Artist: Siegfried Krepp (1930–2013)

Location: Near the entrance of Fennpfuhlpark, Landsberger Allee at the corner of Weißenseer Weg, Große Liegende (Large Reclining Woman), Artist: Siegfried Krepp (1930–2013), Date: 1966–1971, Material: bronze

Large Reclining Woman in the Fennpfuhlpark is all about leisure. The female gure lolls about unabashedly on the ground, visibly enjoying the sun. Her relaxed gaze looks into the distance. One arm supports her body, while the other holds her head. The nely draped folds of her dress and tight-tting fabric reveal the voluptuous curves of her body. Her calves and arms form triangles and diagonals that add dynamic movement to the surroundings. Siegfried Krepp combined elements of classical sculpture with the common design principles of the time: the triangular composition, the rich folds of the fabric, the natural design of the face and body, and the slight exaggeration of the volumes.

The design reects the aesthetic principles Krepp’s teachers – Waldemar Grzimek, Heinrich Drake, and Fritz Cremer, who were important representatives of realistic sculpture in the GDR. But in contrast to female motifs from the 1950s, when images of Trümmerfrauen – female volunteers who helped clear the rubble and rebuild the country – projected the strength of a edgling nation, Krepp‘s sculpture illustrates the enjoyment of the 1960s and 1970s. The femininity of Large Reclining Woman is characteristic of art in the GDR: self-condent, dignied, and humanist.

Station 9: Mädchen mit Ball (Girl with a Ball), Artist: Christa Sammler (*1932)

Location: Stadtpark Lichtenberg, Möllendorffstraße, near the playground, Mädchen mit Ball (Girl with a Ball), Artist: Christa Sammler (*1932), Date: 1965, Material: bronze

Like a first among equals, the bronze sculpture of a girl towers between the tall, slender trees of Stadtpark Lichtenberg. The girl shis her weight onto her left leg while extending her right leg to the rear with her foot pointing outward. She stretches her arms in the air and effortlessly balances a ball on her ngertips, her head tilted back slightly and her gaze xed on the ball. The limbs are abstract, the individual muscles are hardly discernible and the face is stylized. The sculpture seeks to capture a moment of a girl in play: dynamic, emphatic, nimble. Girl with a Ball accords with the East German ideal of athleticism and the antique notion that a healthy mind resides in a healthy body. Girl with a Ball is perfectly placed in a city park designed for relaxation and recreation.

Station 10: Mädchen mit Apfel (Girl with an Apple), Artist: Christa Sammler (*1932)

Location: Nibelungenpark, entrance Dietlinde straße, Mädchen mit Apfel (Girl with an Apple), Artist: Christa Sammler (*1932), Date: 1961, Material: bronze

Barefoot and wearing a summer dress, the gure in the sculpture is a carefree spirit. Her mouth is open and she seems about to take a bite of the apple she holds in her left hand. Why does she hesitate?

For this work, the sculptor Christa Sammler turned to the subject of leisure, a common theme of public art in parks and open spaces. Sammler’s sculpture is a pared-down depiction taken from real life, with a keen understanding of the human body. The triangular composition provides balance, stability, and harmony – a testament to her study with Walter Arnold and Gustav Seitz in the 1950s, leading representatives of realistic sculpture in the GDR.

Girl with an Apple is one of the artist’s major works and has appeared in numerous art exhibitions. The depiction may seem banal, but it may also contain hidden symbolism. The hesitation could be a moment of reection on the part of a young woman, or it may signify the moment before Eve commits original sin.

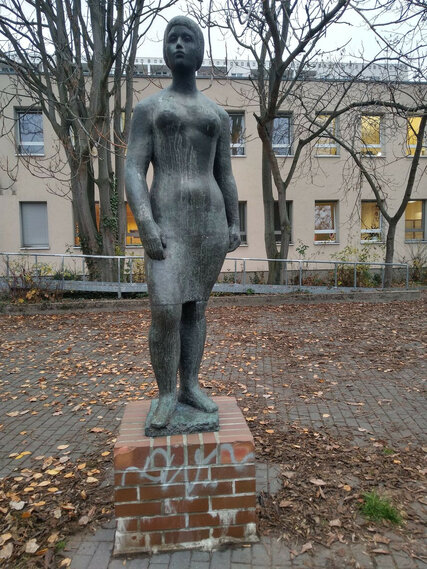

Station 11: Frau (Woman), Artist: Karl Lemke (1924–2016)

Location: Rosenfelder Ring 15, green area in front of the medical center. Frau (Woman), Artist: Karl Lemke (1924–2016), Date: 1975, Material: bronze

The gure that confronts the viewer in Woman is self-condent, strong, and forward-looking. The larger-than-life size and the elevated position reinforce the impression. While a delicate contrapposto – a stylistic device developed in classical antiquity – supplies movement, wide feet serve to ground her, and powerful hands suggest a woman accustomed to taking charge. A round, smooth face and narrow mouth radiate youthfulness; the short hair frames her face. Woman recalls representations of female reconstruction volunteers and Trümmerfrauen that were common in the 1950s. But Lemke seems to have reimagined her gure as a woman from the 1970s, shed of the staid solemnity that characterized the postwar era. The strength she projects is typical of the emancipated and self-assured image of femininity in the GDR.

Station 12: Spree and Havel, Artist: Dietrich Grünig (1940–2020)

Location: Erich-Kurz-Straße 11–13, Spree and Havel, Artist: Dietrich Grünig (1940–2020), Date: 1980–1982, Material: bronze

Two women, one sitting, one reclining, seem to oat in the air as water splashes down around them. The women are personications of the Spree and Havel rivers, which meet near Spandau, on Berlin’s western edge. Like the rivers, the women touch but face in opposite directions. For one woman, the conuence seems to be a delight; for the other, it is a source of unexpected excitement – as their faces and hairstyles show. Dietrich Grünig’s work stands in a tradition going back to antiquity: depicting women as allegorical representations of rivers. Their young, graceful, and athletic bodies allude to the natural strength and freshness of the river water. Likewise, the fountain’s water, which springs from a conical spout into an octagonal basin, is at once invigorating and calming.

The inclusion of art in residential areas and pedestrian zones was characteristic of urban environments in the GDR. Grünig’s work not only enlivens the surrounding public space; it forges a connection to the city and its geography.